This Marion Mets catcher became a world-famous elephant trainer

Roman Schmitt left baseball and Marion to ultimately follow in his father Hugo's footsteps.

Marion Mets Newsletter – Issue 14

Bruised shins. Broken digits. Busted knees.

There’s a reason they call catcher’s equipment the tools of ignorance.

Roman Schmitt likely wished he had some sort of tools – ignorant or otherwise – protecting his body the day an Asian bull elephant charged him, goring his leg, threatening not only his livelihood, but his life.

Roman spent five months in the hospital. He had 19 operations – there were bone, artery and skin grafts – and doctors worried they’d have to amputate his broken leg.

But, seven months out from the accident, he was back at work, with a slight limp, once again in the middle of elephants stomping and circling and about. “Every profession has its dangers,” Roman told a newspaper reporter. “I have respect for them, but not fear.”

His occupations over the 15 years prior to the accident had often placed him in the path of hard-charging land mammals, whether it be a 6,000-pound elephant with piercing tusks or a 240-pound nostrils-flaring ballplayer charging down the third base line.

Before elephants and rhinos, there was baseball

Roman Peter Schmitt caught the eye of New York Mets scouts when he was smacking baseballs around the ballpark as a member of the Riverview High School Rams in Sarasota, Florida in the late 60s and into 1970.

As a senior, Roman led all his teammates with a .455 batting average. With his quick bat, he hit .342 as a sophomore, playing catcher and first base, and .364 as a junior.

“Roman is the best all-around catcher I’ve ever coached,” his high school skipper Clyde Steen said. “No lad ever wanted to play ball more than Roman.”

Following his high school graduation, the 18-year old was set to take his talents about a half an hour south of his home at 318 Howell Place in Sarasota to Manatee Junior College on a full scholarship.

That all changed, however, when the New York Mets, World Series champs in ‘69, selected the slender 5-10, 170-pound catcher in the 16th round, No. 383 overall, in the June 1970 Major League Baseball draft. Roman was considered by coaches and scouts to be one of the best young catchers in Florida.

“It’s all I ever wanted to do,” he said. “My parents want me to go to school, but they also want me to play pro baseball.”

Roman’s mother, Jenny, smiled as she stood behind her son when he signed the contract with New York scout Birdie Tebbetts sitting to his left in a light suit. His father, Hugo, voiced his approval of the phone from Nashville, Tennessee, where he was on the road with Ringling Brothers Circus.

Becoming a professional ballplayer meant Roman had to forgo his college scholarship, but as Tebbetts explained, the catcher received “a satisfactory bonus.”

Tebbets assigned his new catcher to play his first season in Marion, but first he was to report immediately to the New York Mets’ training campus in St. Petersburg, Florida, for 10 days of workouts.

Tebbets, a former big league catcher and manager before hooking on with the Mets as a scout and sometimes rookie league skipper, had his eyes on Roman for a while. “I’m proud to say I’m the scout that signed Roman Schmitt,” claimed Tebbetts, who had managed the Marion Mets in 1967. “He is a fine boy – a good boy – and he wants to play baseball more than anything else. I think the boy can go as far as he wants in this game.”

After a couple of weeks in camp, Roman and his teammates arrived in Marion on June 21, 1970, a Sunday afternoon, just days before the Mets opened the Appalachian League season on a Tuesday night in Bluefield. Terry Christman had been appointed the team’s skipper with director of player development Whitey Herzog visiting Marion to lend his assistance and expertise for the first couple of weeks.

Former big-leaguer hurler Chuck Estrada, who played one year with the Mets, but spent most of his career with the Baltimore Orioles, was to serve as pitching coach, and former New York Yankees infielder and 1964 All-Star Jerry Lumpe was the team’s hitting coach.

The Mets’ 1969 sixth-round draft choice, right-handed pitcher Randy Reynolds, also arrived in Marion along with four players – Gary Betts, Mike Kowalski, Danny Murphy and John Tregilgus – who were a part of the 1969 Marion team that finished second, just a half game out of first place, in the Appy League with 37-32 record.

But as much as Marion fans hoped to see their team win the 1970 title — and keep an eye out for the next big-league star — the Marion squad never could capture the magic.

Not even close.

The Mets finished the season with a dreadful 22-37 record, settling at the bottom of the seven-team league.

“We are all tired from holding up the entire Appalachian League,” Marion Baseball President Bob Garnett joked near the end of the ‘70 season. “In my judgment, Terry Christman did well with the material he had to work with.”

Roman Schmitt didn’t contribute much to the team’s efforts, at least not with his bat. The kid from Sarasota hit just .134 and struck out 38 times in 37 games for Marion.

There was one particular bright spot for Marion, however, in which Roman played a major role.

He was on the receiving end, you might say, when on August 11, 1970, righty Randy Pugh of Calistoga, California, pitched the first ever no-hitter in Marion Mets history. Roman was Pugh’s catcher that night.

Roman had one of his best games at the plate for Marion that night, going 2-for-4 with a couple of runs scored and two runs batted in. Chipping in, too, were Steve Warden, who grew up and played high school ball just across the Virginia-Tennessee border at Sullivan East High School, and Joe Ostrosser, who was just two weeks away from being named the Mets’ MVP. Both had two run home runs to give the Mets a 12-0 win over the Kingsport Royals.

As Pugh’s catcher, Roman played a significant role in Pugh’s commanding performance, one in which the pitcher struck out seven Royals and allowed only three base runners in the seven-inning victory in game one of a doubleheader.

The Mets 1970 season ended in late August, and so did Roman’s time in the Southwest Virginia town. Shortly thereafter, he joined the National Guard, “perhaps to avoid being drafted to the Vietnam War,” his son Ryan Schmitt told me.

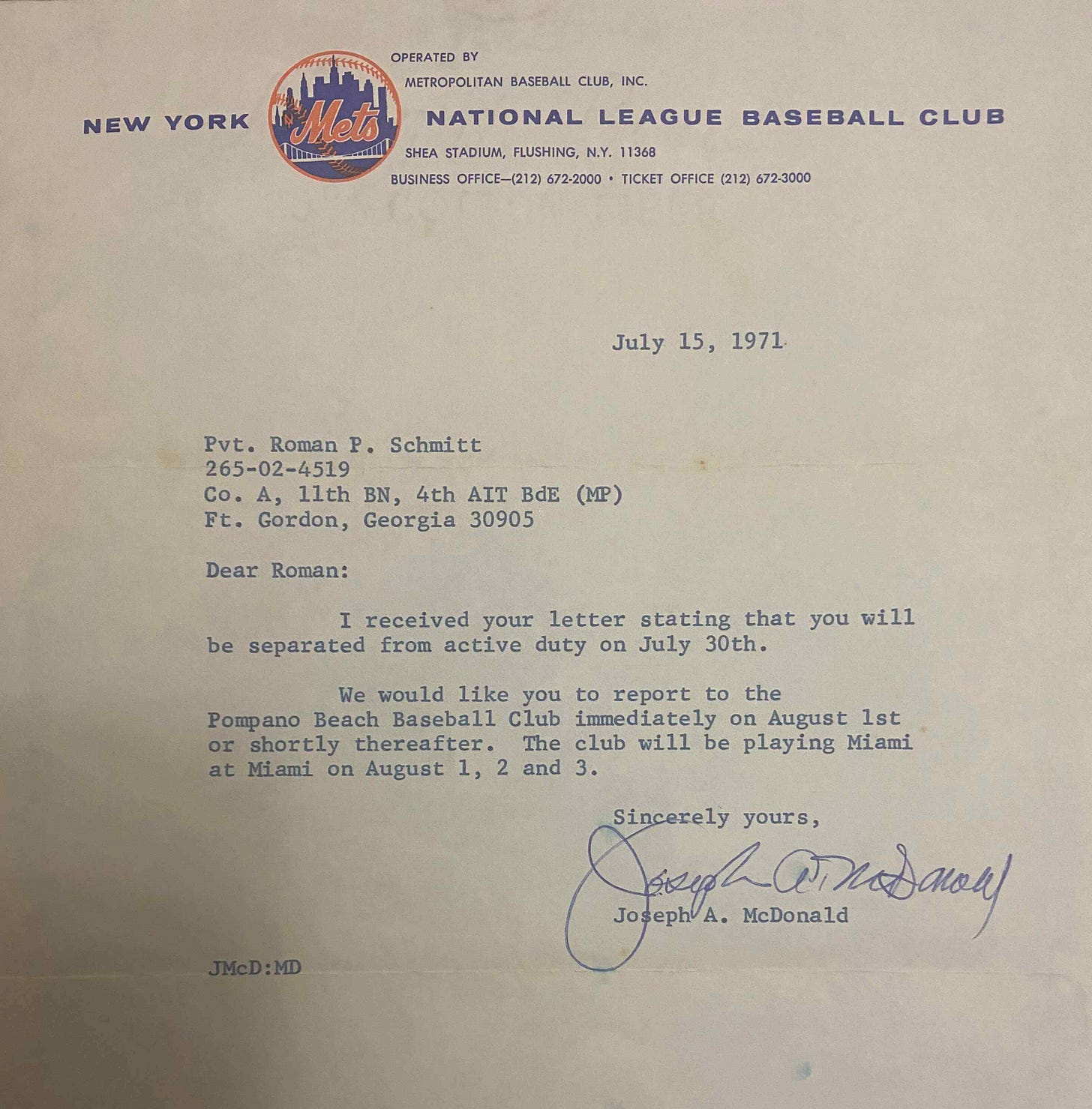

Despite his down year at the plate in Marion, the New York Mets saw Roman Schmitt’s potential. The following summer, in 1971, the New York organization invited him back, this time a little closer to home and one rung up the minor league ladder from the Marion Mets.

“Would like you to report to the Pompano Beach (Florida) Baseball Club immediately on August 1st or shortly thereafter,” New York Mets minor league Director Joe McDonald wrote to Private Roman P. Schmitt on July 15, 1971. “The club will be playing Miami at Miami on August 1, 2 and 3.”

Roman made it to Pompano Beach, but played only one game for the single A Mets team there. He had one hit, scored a run and knocked home another.

After that game, his baseball career came to an end. He returned home heartbroken.

The family business

Hugo Schmitt hurried through snow and ice along the streets of Hamburg, his labored breath crystalizing in the bitter cold night air while commanding a small herd of five elephants - Icky, Karnaudi, Minjak, Mutu and Sabu – to their safety aboard a train headed for Sweden. Among all the objects falling from the sky, snow was the least of his worries.

As sirens blared through the night sky one November night in 1944, Allied forces flying overhead dropped bomb after bomb, obliterating parts of the German city.

Moments after Hugo’s brave and heroic escape, the circus house roof burst into flames.

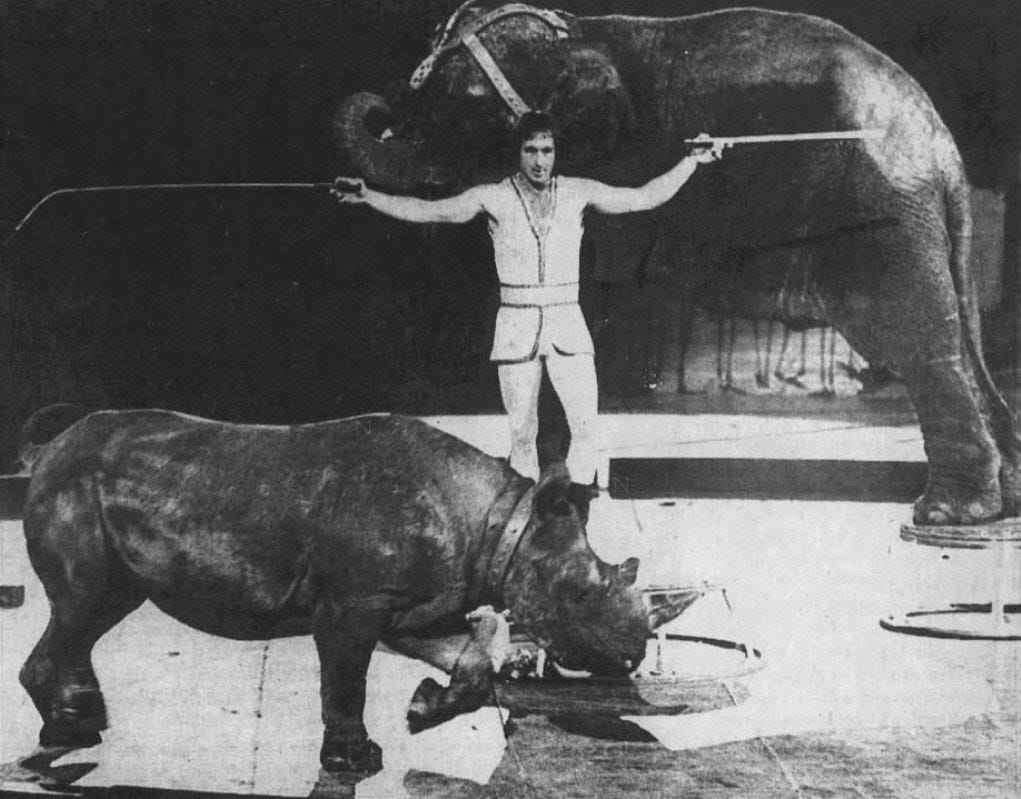

A few years later, the Swedish government confiscated and planned to sell Hugo’s beloved elephants, their “spoils of the war,” newspapers there reported. Hugo was devastated. The Billboard, in its March 8, 1947, ran a three-paragraph article with the headline: “Unhappy elephant trainer releases five bulls on street.”

“They were trying to separate his animals during the war, and he [Hugo] told them ‘No, you can’t separate them, they’ll die,’ said Hugo’s granddaughter and Roman Schmitt’s daughter Megan Marovich. “So, he turned a herd of bull elephants loose on his town.”

The elephants ran wild, “breaking lampposts and terrorizing citizens,” The Billboard reported. Police, unable to corral the animals, eventually convinced Hugo to reign them in.

He did.

“The state is making a grave mistake in selling them,” Hugo said with tears in his eyes. “They have been trained together and love each other. If they are parted, they will die.”

Better news for Hugo and the elephants arrived soon, though, in the form of John Ringling North, who journeyed to Sweden to purchase the elephants on the condition that Hugo move to the United States to train the animals along with the 38 already owned by Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey Circus.

For years, Hugo Schmitt made a living as a renowned circus elephant trainer. In 1953, President Dwight Eisenhower called Ringling to request the best elephant trainer in the world to be part of his inauguration festivities. Ringling, of course, sent Hugo.

“The elephant is the Republican party symbol, after all,” the trainer said.

Hugo worked with Ringling until 1971, training animals and performing shows that included a wide variety of acts that captivated audiences. He once trained a zebra to stand on the back of a reclining elephant and, speaking a combination of English and German, he instructed a South American llama to leap over an elephant’s back. He once boosted Marilyn Monroe onto the back of a painted pink elephant during one of his performances at Madison Square Garden in New York City.

“He had a voice that came through and they loved him,” Hugo’s wife, Jenny Schmitt, once explained to a newspaper reporter. “They respected him – and they have to – otherwise you’re gone.”

Hugo’s 25-year career with Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey Circus, nearly came to an abrupt ending from the tusks of one of his beloved creatures. Once, a female elephant charged Hugo and violently tossed him into a truck. He suffered a punctured lung, broken ribs and a snapped collarbone.

It seems the lure of show business and roaring crowds – far bigger and more boisterous than those in Marion – topped any trepidations his son Roman may have had about transitioning from baseball and into his father’s profession.

Soon after his release from the New York Mets organization and a brief stint in the military, Roman began training with Hugo, learning the ropes of elephant training with the traveling circus. It didn’t take long for Roman to get his own gigs.

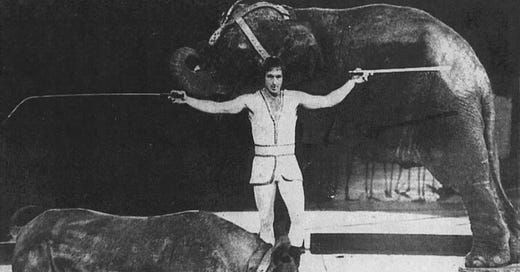

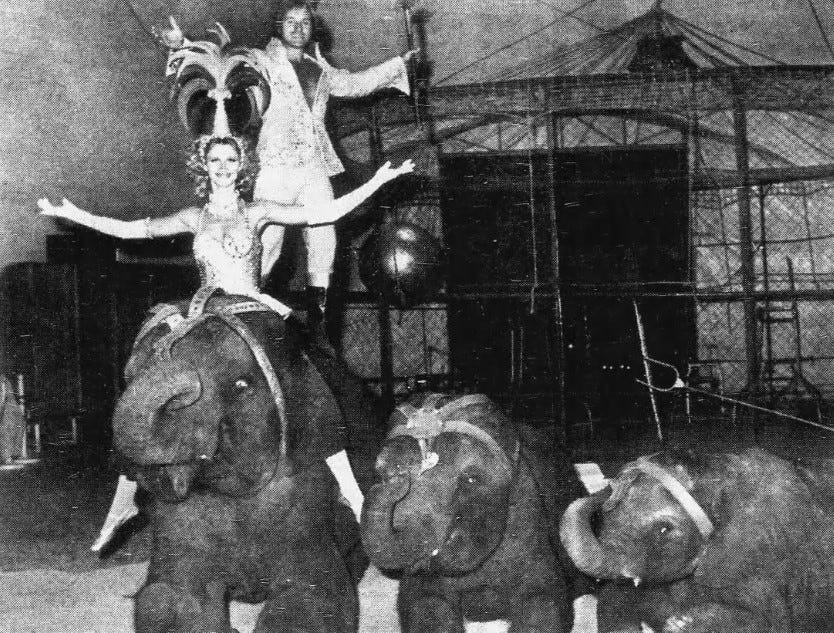

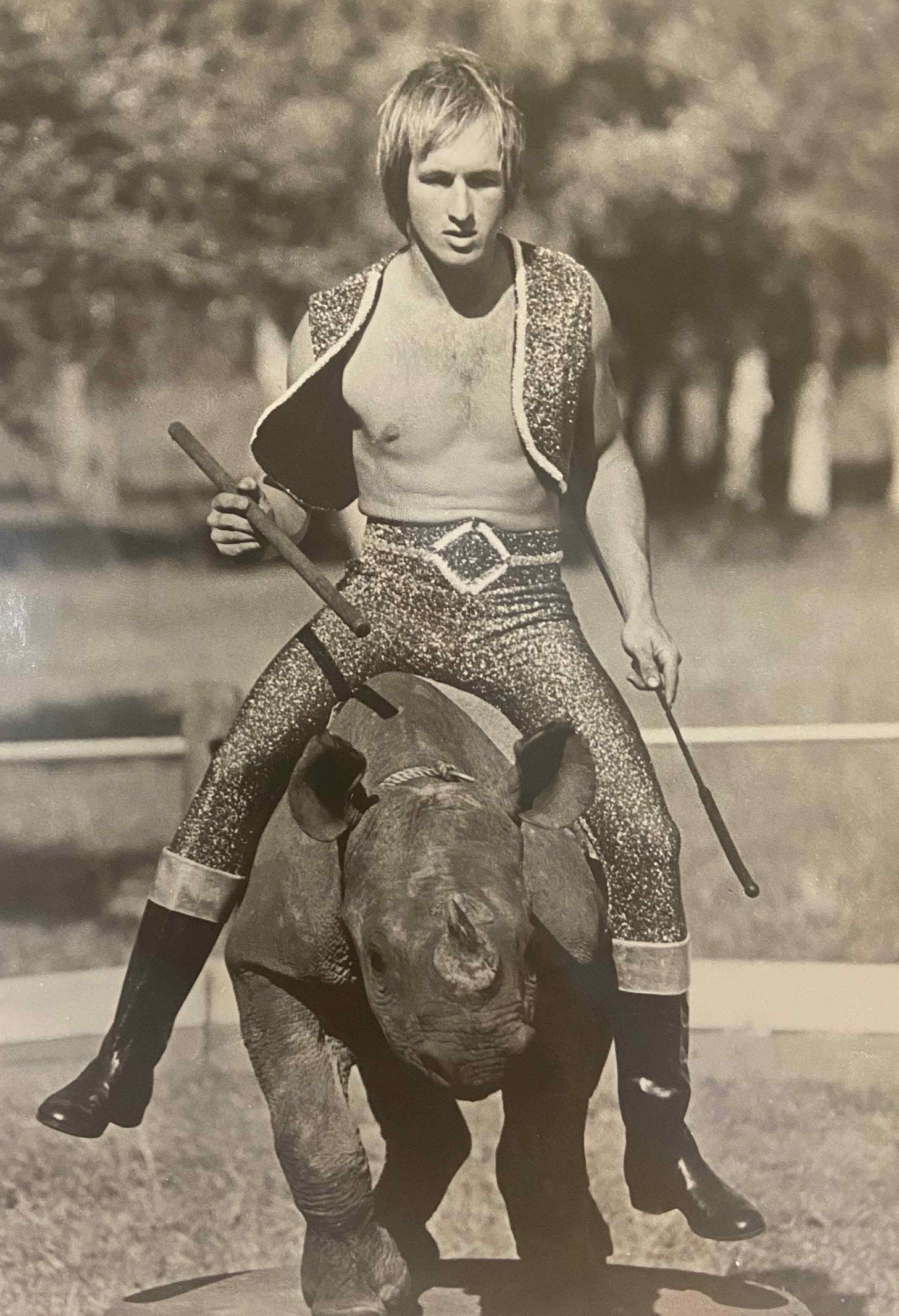

The catcher-turned-animal trainer dazzled audiences with spectacular performances. Some nights, circus goers might see a tiger hitching a ride on an elephant’s back. They might also see Roman’s black rhino, Kenya, working tusk-in-tusk with an Asian elephant named Birka.

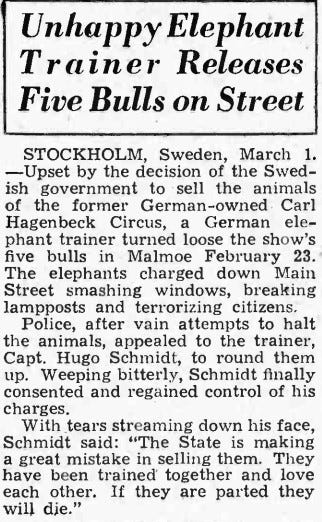

With wife, Jean, by his side, or standing atop elephants, Roman worked at Circus World near Orlando, Florida, and started the theme park’s elephant breeding program. Years later, he did the same at Busch Gardens animal theme park in Tampa, Florida.

“It was really cool when we were kids,” Marovich recalled. “My uncle [Eddie Schmitt] lived behind us, and he had the tigers, and my dad and my mom had the elephants. We felt we were so mistreated as kids because we couldn’t have friends over because it was such a liability. But we had the animals there, and it was really interesting.”

Roman’s success nearly never happened. A little more than a decade into his new profession, an elephant bull named Toomai gored his leg as the two walked out of a barn into the pasture to prepare for one of their daily shows at Circus World around 8 a.m. on a Thursday on April 14, 1983.

As blood poured from his broken leg, Roman limped out of the pasture and fell to the ground, bumping his head.

“A freak accident,” is how Roman later described the near-fatal attack from an overzealous pachyderm. Circus World spokesman Frank Langley said the same.

“If the elephant had attacked him, I guarantee you he wouldn’t be with us today,” Langley said as Roman lay in Winter Haven Hospital the next day, after surgery that, the circus spokesman said, involved tying together “arteries and veins and tissues.”

One of his legs “was very messed up,” Ryan Schmitt, Roman’s son, told me on the phone. “There was a cavernous indention that went up the entirety of the inside of his leg. There was a huge valley in his leg.”

Ryan, who was born to Roman and Jean in 1991, does not remember much about his father. He remembers the scar – “It was weird,” he said, but most of the knowledge of his father’s circus life comes from handed-down stories and research that he a his sister, Megan, assembled into a scrapbook.

Roman Schmitt died in May 2001 of liver failure, Ryan said, at age 49. His legacy in the circus far exceeded his baseball exploits in Marion and elsewhere. One of his Marion Mets teammates remembers Roman fondly. On the diamond, “he was a good catcher, and a good pull hitter,” said Warden, the infielder from Bluff City. Tennessee.

“But also, he was a really nice guy, and a good teammate.”

Connect with Marion Mets on Facebook

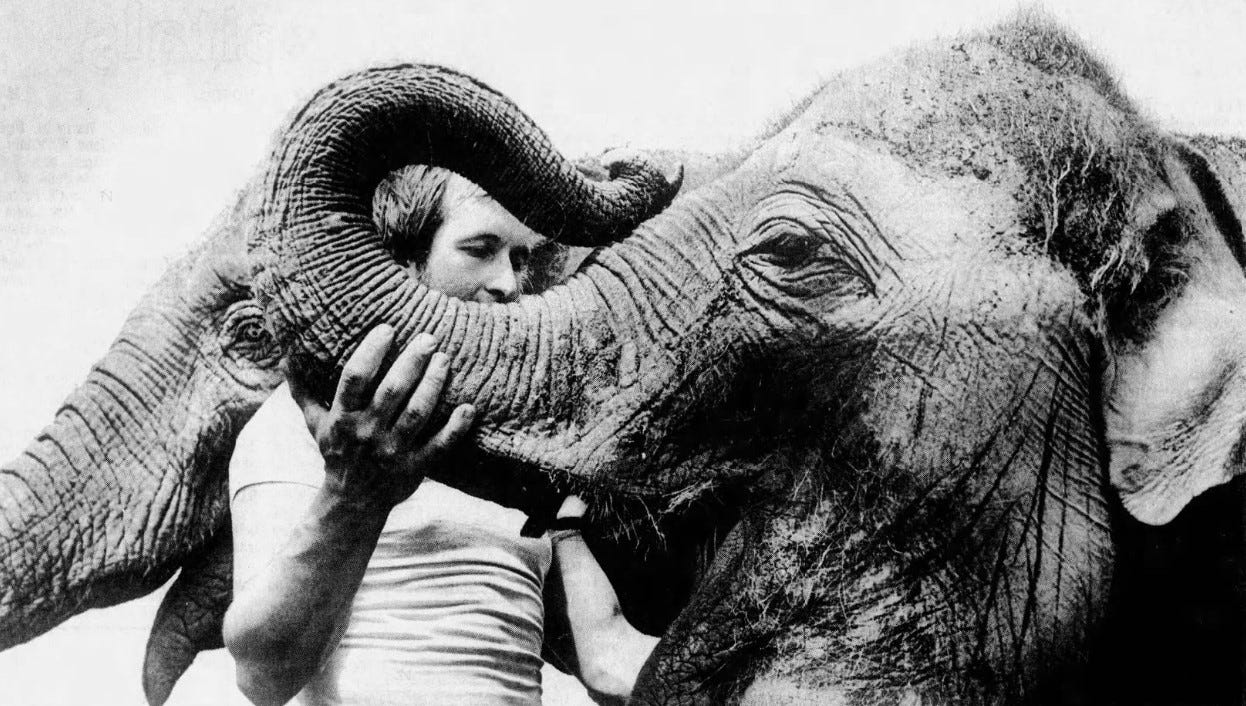

Bonus photo!

Is it me, or does it appear Roman is training this elephant to squat into the catcher’s position?