Marion Mets Newsletter – Issue 12

Larry bounced out of his crouch behind home plate, tossed aside his mask and camped beneath the falling sphere.

A few feet away, a Wytheville Braves batter sprinted down the 90-foot white line after sending a Baltimore chop sky high, or at least high enough to create a sense of urgency between Larry and his pitcher. One of them needed to grab the ball and quickly fire a bullet to first to force out the batter in this close Appalachian League contest.

“I got it,” Larry shouted to Marion left-handed pitcher Mike Anderson, who raced off the mound toward the ball, toward Larry.

A light rain fell on this warm, late August 1971 evening at Withers Field in Wytheville, Virginia, making the dirt around the plate a little sticky, the grass a little slippery.

As Mike and Larry reached for the ball, the Braves’ batter sped closer to first base, hoping to beat the throw.

But, the ball never arrived.

Mike slid into Larry, bending the catcher’s knee in a direction it was not built to bend.

Several feet away, in the Marion Mets’ dugout, skipper Chuck Hiller heard something.

Pop!

It was loud.

It was Larry’s knee.

“At first, I didn’t feel it,” Larry Berra recalled on the phone nearly 51 years later. “I just fell to the ground.”

Hiller, the Marion Mets manager, rushed out to help his catcher. Larry began to push himself up when he felt Hiller’s hands holding him down.

“What’s the matter?” Larry asked.

“Don’t move,” the skipper said. “We heard something pop in the dugout.”

Soon, Larry was in the Wytheville hospital, a short drive from Withers Field. A doctor there looked over the catcher’s banged up knee – even at 22, Larry’s knees had been through a lot – and said “I’m not equipped for this. All I can do is brace you up and send you home.”

Larry’s season ended that day. So did his time in Marion.

Weeks later, he journeyed back to his New Jersey hometown, catching a ride from his famous father, Yogi Berra., and mother, Carmen, who had flown to Smyth County for a couple of days to help the local team boost attendance in the waning days of the season.

Their presence caused a stir around town and brought throngs of people to Marion Stadium for an attendance booster night. Delighted fans smiled and laughed through a couple of hours of baseball, clambered for pictures and autographs from Yogi and won prizes from hair spray to helicopter rides.

When it was over, the Berras drove their son home, his injured leg propped up in the back seat of his royal blue 1969 Rally Sport Camaro with a convertible black top and hideaway lights.

‘If the world were perfect, it wouldn’t be’

You’d think it would be quite difficult to walk out onto the grass of rickety old, poorly lit ballparks night after night in small Appalachian towns with two bad knees and what some people in positions of authority considered a weight problem.

On top of that, there was the chore of living up to your famous ball-playing father’s name.

“Sometimes, I wish my name was Larry Jones,” Larry Berra Jr, the son of Hall of Fame baseball player Yogi Berra, confessed in the summer of 1971 to a New York Daily News writer, who was in Southwest Virginia to chronicle the happenings of the Marion Mets, 570 miles away from their big league parent club in Queens, New York.

Larry doesn’t remember making the Larry Jones comment. “It wasn’t as bad as you might think,” he said, talking about playing rookie-league ball while being the son of a beloved baseball legend and cultural icon.

He did confess, however, to one lapse in judgment one night in Wytheville.

Again, it was Wytheville.

“So, a guy [in the stands] kept bugging me. He said I couldn't hit like my father,” Larry recalled with a chuckle. “I turned around and said ‘if I could hit like my father I wouldn’t have to listen to you.’”

Chuck Hiller, again to the rescue, sprang from the dugout, this time for a quick word of advice for his young ballplayer. “You can’t say that to people,” he explained.

Lesson learned.

Frustration may have gotten the best of Larry that night, but very little of that, he said, came from bearing the Berra name.

The New York Mets signed Laurence Allen Berra II as a 22-year-old free agent catcher out of Montclair State College in June of 1971. A week earlier, the Mets drafted and signed another junior: Gil Hodges Jr., son of former Brooklyn Dodgers legend Gil Hodges, who, at the time, was manager of the New York Mets.

Whitey Herzog, the New York team’s’ director of player development, sent them both to Marion to begin their professional baseball journey. Larry reported to Marion weighing 214 pounds, a little heavy for Hiller’s liking, and so it took the catcher some time to get into a game.

Hodges Jr., meanwhile, slugged his way out of Marion quickly. He was promoted to single A Pompano Beach, Florida, after hitting a robust .429 in only six games with the rookie league Mets.

For Larry, it was more of weight and see process.

“He will get in there when he gets down to 200 pounds,” Hiller said to a newspaper reporter in early July, a few weeks into the Appalachian League season. By then, Larry was weighing in at 205.

Trying to get his weight down, Hiller and Herzog put Larry through strenuous workouts.

“We did double sessions,” Larry said, recalling preseason workouts in Marion. “We did a lot of running.”

On the phone in June 2022, Herzog chuckled when asked if he remembered the situation.

“Well, he didn’t look like an athlete then,” Herzog said. “But, he really had a very bad – I don't know which one, right or left – but a terrible knee problem.”

Both Hiller and Herzog played eight years in the major leagues and had strict philosophies about what it took for a player to take his game to a higher level. In 1962, Hiller, a second baseman for the San Francisco Giants, became the first National League player to hit a grand slam in the World Series. Herzog played professionally for the Washington Senators, Kansas City A’s, Baltimore Orioles and Detroit Tigers before becoming a Hall of Fame manager in St. Louis.

“I wasn’t feeling very well,” Larry recalled. “They sent me to the doctor [in Marion] and the doctor said, ‘He’s a big kid; he needs to be over 200 pounds. You got him at 190. He needs to be more nourished.’ After that, I gained a little weight back and did just fine.”

The menu at the Broad Street Tea Room downtown may have helped. “That was the best fried chicken I ever ate,” Berra recalled. “We used to go there every night, and I’d eat fried chicken all the time.”

Soon, after a few chicken plates, Hiller began penciling Larry into his lineup, typically hitting in the middle of the order. But, he only played in a handful of games before the knee injury.

Larry’s most memorable hit as Marion Met was a home run – it was the only home run of his brief two-year minor league career – and he smacked it off a Louisiana pitcher who major league baseball fans would soon enough know by two nicknames, Gator and Louisiana Lightning.

The Johnson City Yankees rolled into Marion on July 14, 1971, to begin a four-game road trip after a scarce night off. The Mets jumped on the Yankees early in the game when Luis Garcia doubled in the second inning, garnering applause from the Marion faithful.

Larry walked up to the plate looking to give the hometown fans even more to root for.

And, he did!

They roared when he swung his bat and deposited Johnson City hurler Ron Guidry’s pitch over the wall, over the Baldwin’s department store sign on the wall in left center, out toward the Brunswick plant.

Guidry, as many baseball enthusiasts know, soon left Johnson City, played in various other minor league towns before settling into an all-star career for the New York Yankees, with whom he won two World Series titles.

“I think it was just a fast ball, down low and inside, which was one of my favorite pitches to hit,” Larry said, recalling the pitch he hit off of Guidry. “Ron didn’t have a slider yet,”

Guidry and Larry agree it was a fastball, but they differ wildly on where the ball landed.

“Oh, yeah. I remember it,” Guidry said on the phone on January 26, 2023.”But, he [Larry] didn’t tell you how far he hit it.

“It only went about 215 feet down the line. Yeah, he did hit a home run, but it didn’t go very far, Guidry said laughing. “It wasn’t like a monumental blast, you know.”

Larry admitted in a separate phone call that he did not make many trips to the plate. “So,” he said with a laugh, “I can remember just about every at bat I ever had.”

During his short time in Marion, Larry hit for a .150 batting average, which was well below standards, especially at the rookie league level, but it can be difficult to find your groove in only 15 games. In addition to the home run off Guidry, Larry managed one double, 8 RBIs and an on-base percentage of .190. One of his highlights, he noted, was catching Ed Burgy the night the Mets’ righthander from Bellaire, Ohio, struck out 20 Bristol Tigers, and gave up only three hits and a walk in front of the home crowd in a 5-1 win.

The Wytheville game, where he banged up his knee, was Larry’s last as a member of the Marion Mets, and close to the last of his short career. His knees made certain of it.

He knew back then there was no simple solution, no easy fix. He already had one knee surgery, the first of many more to come, and “had all kinds of treatments just to keep me playing college and high school ball.”

“Basically, that knee injury ended my career,” he said.

‘I want to thank you for making this day necessary’

For Smyth County News editor Barbara Hawkins to mention it in her “Town Talk” column, you knew Yogi’s visit to Marion would be the talk of the town.

It was Yogi Berra. Of course, everyone was talking.

“Area residents will have a chance to boost the Mets organization and see Yogi Berra later this month,” Hawkins typed on the editorial page. “Berra, who has a son playing for the local team, will be a special attraction on ‘Boosters Night.’”

Marion Baseball Inc. placed ads in the Smyth County News, too, promoting the booster event. One ad listed a plethora of prizes to be given away, such as a gallon of paint, a baseball glove, a savings account at the Bank of Marion, a broach, a Pepsi picnic cooler, three gift certificates for one box of shotgun shells, records, cash, a Zippo lighter, an ashtray desk set, coffee maker, and perhaps the grand prize, a helicopter ride for two over Marion. Or, was the grand prize the late 60s model American Rambler given away by Jennings-Warren Motor Company?

Larry’s now lost season turned into a big opportunity for Marion and its Mets.

Bob Garnett, president of Marion Baseball, hoped Yogi’s arrival would make up for slumping attendance. In his weekly Smyth County News column, which ran on the sports pages, Garnett blamed the soggy summer of ‘71 weather for the attendance drought.

“The rains have hurt our attendance and we really need a good ‘Booster Night’ to close our season,” Garnett wrote, encouraging fans to turn out.

Rainy days and nights can always put a damper on ballpark attendance, but the Marion Mets were playing just under .500 baseball. They were 30-33 the night Yogi arrived to watch them play the Johnson City Yankees, and with four games to go, attendance was down by almost 5,000 paying customers from two years before when the Mets came up only a half a game short of winning the Appalachian League south division title.

A visit from the popular Yogi Berra could certainly go a long way toward increasing the number of paying customers walking through the Marion Stadium gates near season’s end.

*****

Perhaps it's worth noting here that another Appalachian League team down Interstate 81 tried, it seems, to lure Yogi to its ballpark, too.

The Kingsport Times-News told its August 24, 1971 readers to be on the lookout for Yogi at the ballpark that night.

“In all probability, baseball great Yogi Berra, former player for and manager of the New York Yankees and now a coach with the [New York] Mets, will be in Kingsport tonight,” the paper reported. “A spokesman for the [Kingsport] Baseball Boosters Club said it isn’t definite, but he [Yogi] is expected in the area and just might pay J. Fred Johnson Stadium a visit.”

But, Yogi never made it to Kingsport. Instead, he was at Bob Garnett’s house that Tuesday night “Swirling vodka around ice cubes in his high-ball glass,” recalled Garnett’s son, Lewis, who was 19 at the time and home from college on summer break.

“The melting ice cuts the vodka just enough,” Yogi explained to Lewis that night, relaxing in the Garnett house at Mt. Carmel.

Meanwhile in Kingsport, an unidentified man pretending to be New York Mets superstar outfielder Cleon Jones “paraded through the ballpark stands,” the Times-News reported, signing autographs for children.

*****

“Yogi will be available to autograph balls and score cards for the fans and pose for pictures. So, be sure to bring your camera,” Garnett instructed in his weekly column.

To paraphrase the voice emanating from the Iowa corn field in Field of Dreams: If you plan it, they will come.

The plan worked to perfection, it seemed, because there he was. Yogi Berra, a lovable character on and off the field, known as much for his affable personality and “Yogi-isms” as he was for his 10 World Series titles, his 15 All-Star selections, his three MVP awards, and for being the catcher behind the plate for Don Larson’s perfect game in the 1956 World Series.

He was there, Yogi Berra, at the ballpark in downtown Marion, Virginia, on August 25, 1971, in front of thousands of fans, far less than the nearly 60,000 he was accustomed to seeing during his playing days with the New York Yankee, but no less delighted.

“It was as packed as you could get it,” recalled Gene Dalton, who was at the game on assignment to photograph the game and festivities for the Smyth County News. “People were standing behind the dugout. It was full of people wanting to see Yogi. People who couldn’t get seats sat in folding chairs.”

It didn’t matter that it was the last night of summer vacation and Smyth County school kids returned to class the next day. It didn’t matter that it was the middle of the week, a Wednesday night, and the next morning meant heading off to work again.

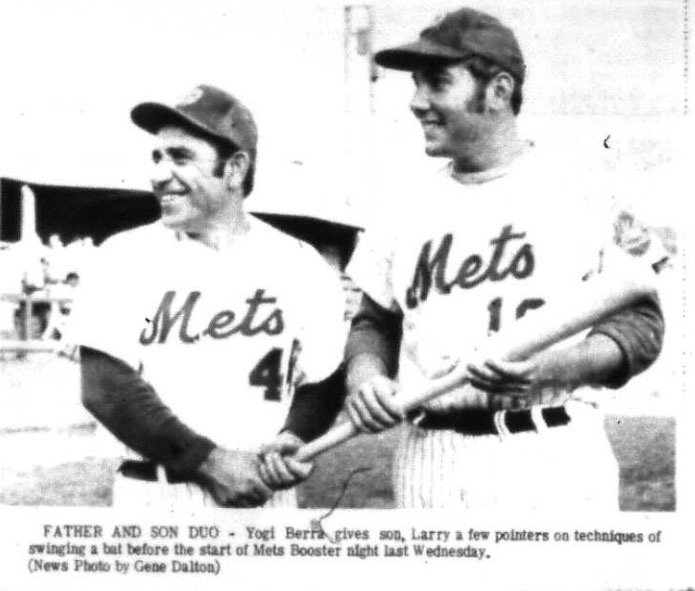

As people settled in, taking their seats on the bleachers and lawn chairs or standing elbow-to-elbow along the fences behind the dugouts, Yogi and Larry, both in full Mets-pinstripes uniforms with matching sideburns and ear-to-ear smiles, posed for pictures on the field with both holding the same bat.

Yogi spoke with the press, complimenting Marion’s clubhouse facilities – “we were lucky to find a place to hang our socks,” he said of his own minor league playing experiences. The senior Berra also explained that when he “landed at Roanoke Airport, it was the first time he had been “back in Virginia, in this area, since 1943… except for an exhibition game at Lynchburg several years ago.”

Shortly after Yogi posed for pictures shaking hands with U.S. Senator William B. Spong Jr., during the pregame festivities, Chad Baxter, a member of the Marion Jaycees, walked onto the field, dapperly decked out in dark pants, a white short-sleeve shirt and slim dark tie. He presented the team most valuable player trophy to Isaac Small, a speedy center fielder from DeLand, Florida. The two shook hands and walked off the infield. Moments later, the home plate umpire signaled “play ball,” and Marion righthander Greg Pavlick wound up and threw the game’s first pitch at 7:45 p.m.

Pavlick pitched well early in the contest and held Johnson City scoreless through five innings. Marion’s bats were relatively quiet, too, until the bottom of the fifth.

The Mets put five runs on the board that inning thanks to timely hitting from the MVP Small and shortstop John Busco. Free passes from Johnson City pitcher James Alexander, helped Marion too, as did fielding miscues by the cellar-dwelling Yankees.

It was getting late early for Johnson City.

Throughout the game, trivia questions blared over the ballpark speakers. Answering a question correctly was the ticket to one of the many coveted prizes. A helicopter ride. An oil change. A can of hairspray.

One of those questions, and perhaps many others, connected to someone at the ballpark that evening.

“They asked about a San Francisco Giants player hitting a grand slam in the 1962 World Series,” recalled Bill Earp, who at age 11, was in the Mets’ dugout as the team’s batboy. “[Marion manager Chuck] Hiller told me it [the answer] was him and to go claim the prize. I didn't believe him. When they announced the winner, he said, ‘I told ya kid, shoulda listened.’"

In the midst of conniving curveballs and tricky trivia, the cheerful crowd could sense an easy victory as many kept a gleeful eye on Yogi sitting with Marion players inside the dugout.

That’s where Dalton and his camera found the guest of honor.

In the dugout, he also found a man named Cecil, who if Dalton remembers correctly, was “perhaps a scientist,” but for sure “a brilliant man,” he said. Cecil often roamed the stadium grounds, Dalton recalled one December 2022 day sitting in the Marion Starbucks.

“When I was photographing Yogi and some of the players, Cecil came and sat beside Yogi,” Dalton explained. “Cecil opened a bag of chips and put them in Yogi’s lap. Yogi looked at him like, ‘Who is this guy?’ Then, they sat there watching the game, Yogi was eating the chips and Cecil was talking to him. This went on for a little bit, and then Cecil got up and left. Yogi sat there and ate the whole bag of potato chips.”

As Yogi crunched, Johnson City began to put the squeeze on the home team, scoring four runs in the top of the sixth, to cut the Yankees’ deficit to 5-4.

The Mets answered with a run in the bottom of the sixth. Johnson City got two back in the top of the seventh to tie the game at 6-6.

But, that was as close as the Yankees from Tennessee could get.

Marion scored two in the bottom of the seventh when Otto DaCosta tripled. He was 2-for-5 in the game. “I recall being on a very hot streak in late August,” texted DaCosta, who a few years after his baseball playing days worked as an architect in Marion.

The Mets constructed another run in the bottom of the eighth and then held Johnson City scoreless in the top of the ninth. Tony Maya, Larry’s Marion roommate, tossed the last pitch of the night at 10:35 p.m., and after 2 hours and 50 exhilarating minutes, the home team emerged victorious.

Marion 9

Johnson City 6

After the victory, there were a few more handshakes, and backslaps and pictures left to be taken, and enough smiles flashed to illuminate the night sky over Marion, long after the stadium lights had been switched off.

‘The future ain’t what it used to be’

Soon after Larry arrived back home in Montclair, New Jersey, he paid a visit to the New York Mets’ team physician.

“He looked at it [knee] and wanted to mend it up,” Larry recalled. “Back then they [doctors] didn’t do too much. They told me not to do anything for a couple of months.”

Larry followed that advice, and, he recalled, “it actually felt better for a little bit.”

He started playing baseball again early in ‘72. He went to spring training with the New York club, fared well there, but played only seven games in the minors that season, five in Pompano Beach, Florida, and two in Batavia of the New York-Pennsylvania League.

“The more I caught, the more I could feel the knee react,” Larry said.

One night after catching a game in Batavia, “I woke up the next morning and my knee was the size of a basketball.”

Larry had a frank conversation with Whitey Herzog, the Mets player development director at the time, about his injury concerns and his future. “Be honest with me, Whitey,” Larry said to Herzog. “I’ll give it a go, but if I’m not good I want you to tell me right away, and I’ll believe you.”

It wasn’t good.

“I could just never get it back,” Larry confessed. “I lost my ability to step to the outside part of the plate. I always liked hitting to right field, but I couldn’t get my leg to step toward first base. I was afraid to do it because I felt like I was going to fall.”

Larry then counseled with the orthopedic surgeon who performed the first operation on his leg in 1967, when Larry was about 18 years old and still in high school.

“He looked at me, and said, ‘Jesus Christ! What did you do to your leg?’”

The surgeon informed Larry that he could perhaps fix the knee well enough for him to play a couple of days a week. “That doesn't do me any good,” Larry replied. “I want to play!”

In September that year, an Associated Press reporter visited Yogi and Carmen Berra’s home and found a somber Larry on crutches. “The doctors tell me I will never play baseball again,” Larry said to the reporter. “They [surgeons] took out everything – cartilage, bone, gristle. You name it, My career is over.”

Yogi, however, offered some encouraging words, telling his young son to look no further than guys like Mickey Mantle and Joe Dimaggio and Joe Namath who overcame injuries to not only play, but to have hall of fame careers.

The pep talk encouraged Larry in the moment.

It ain’t over ‘til it’s over, you know.

But, Larry knew soon enough.

It was over.

By late summer of 1972, his baseball career had come to an end.

‘When you come to a fork in the road, take it’

When Larry was 16 years old, he asked his father for $5.

“Get a job,” the senior Lawrence Berra said lovingly, but matter-of-factly to his son.

So, he did.

Larry walked around the corner from his home, and asked a friend’s father for work at his construction business. He started a couple of weeks later. Larry poured marble flooring – “it’s grueling work,” he said – and worked at the company through high school and college while also, of course, playing baseball. He was all-state at Montclair High School and, for a while, held the team record for career RBIs at Montclair State in New Jersey.

One day on the job, Larry’s boss offered to move him into an office position to learn marketing, advertising, reading blueprints and all the intricacies that come with running a successful business.

But, office work wasn’t for Larry.

“I begged him; I said ‘I don’t want to go into the office. I love working out here with the men and working physically.’” Larry recalled. “It was the best shape I ever got in my life because everything I touched weighed 100 pounds or more.”

Larry worked for the company for nine years, and then had a partner in the same line of work for 30 years before moving on to start his own business.

“I’m getting to the point where I’m done,” he said on the phone in May 2022, looking ahead to retirement.

When Larry slid and bumped knees with Mike Anderson that damp, August 1971 day in Wytheville, it spelled the beginning of the end to his professional baseball aspirations.

But, it didn’t keep him off the ballfield. His work there was not done. May never be.

“Yeah, I play senior softball; I play 150 games a year,” he said.

One hundred and fifty games a year seems incredible, especially on knees that have endured seven surgeries, including two replacements, most recently the knee he injured in Wytheville.

“Plus, I get what you call ‘old-age things.”

*****

Larry spent only three months in Marion, but it’s a town that forever lives in his memory. He still occasionally browses the internet for photos of Marion Stadium, the place he hit his only minor league home run, the place where he caught Burgy’s 20 Ks with his Spalding mitt – just like his father’s – days before his knee buckled, ending his season.

He seems to remember every last detail of the town. He remembers the poor lighting, not just in Marion, in most Appalachian League ballparks.

He still remembers reading mystery novels on the bus trips to places like Johnson City and Kingsport and Covington and Pulaski and Bluefield, where he enjoyed the “beautiful view of the mountain” from behind home plate as well as the clubhouse that had to be checked for snakes after a rain.

He remembers the movies, off-night Monopoly games with girls in town, the 3.2 beer –”that’s all we could get because it was a dry county,” he said – the Tea Room chicken, and the sweet hospitality showered upon him and his family.

“I remember getting there the first day,” he said, “and going to the Lincoln Hotel.”

Though her name escapes him – “That was 50 years ago,” he reminds me – Larry will never forget the lady he and his roommate, Tony Maya, lived with and the sandwiches and soda she’d leave out for them to devour after home games and late night road trips.

“She was one of the nicest ladies I ever met. But, she didn’t put up with any nonsense. You couldn’t have any liquor in the house, no girls, nothing,” Larry reminisced with a laugh.

“I loved the people there in Marion, and I loved playing there, too,” Larry said. “And, I remember it all like it was yesterday.”

Before you go, this is my reminder that I’m always looking for stories about the Marion Mets. If you were a player, fan, ball boy, concession stand worker… anything… and have a story to share, I’d love to talk with you. You can reach me at chadoz97@gmail.com. Also, if you see something I missed or simply got wrong, send me a note.

And don’t forget to Connect with Marion Mets on Facebook

Chad, I love reading your stuff. You’re a talented writer, a great interviewer and have a knack for getting to the nut of human interest. Another great job. Oh, and the Yogi quotes sprinkled along teased the reader along. Smart story design.

As always, very well written, detailed and flavorful. Thank you for capturing our history.