Marion Mets: Hospital edition

Thump on the head sends Mets’ centerfielder to hospital. Plus, don't kill the ump!

Lou Pacchioli kicked up a cloud of dust diving back to first base. Less than an hour later, he landed on his back in a squeaky-clean hospital room three miles down the road.

The speedy Marion Mets center fielder had just received a free pass to first from Johnson City Yankees’ pitcher Donald Mulhare in game two of a doubleheader on a humid night at the East Tennessee ballpark. Marion had taken Game 1, 4-3, but wasn’t having much luck getting runners on base against the hard-throwing righthander.

The game was scoreless, and the Mets were hitless, when Pacchioli came to the plate in the top of the fourth inning.

“This guy [Mulhare] walked me on four pitches that I didn’t even see,” said Pacchioli, the pride of Pennsylvania’s Lehigh Valley, in a January 2021 phone interview. “He threw that hard!”

A couple of weeks before this July 14, 1965 contest, the Johnson City Press spotlighted Mulhare in one of its “Know Your JC Yanks” features and reported that the 19-year-old from Mt. Kisco, New York had “good control, and assortment of pitches, curves and fastballs…”

Mulhare’s control went astray when he threw over to first, trying to keep Pacchioli close to the bag. That season, Pacchioli would steal 36 bases while splitting time between Marion and Greenville, South Carolina.

“He [Mulhare] threw over and threw wildly and hit me right in the head,” said Pacchioli, who had been sent down to Marion from the New York Mets’ single A Greenville farm club to “learn to switch hit,” he was initially told.

Marion players didn’t wear helmets when running the bases. “You were lucky if you wore a helmet to bat,” Pacchioli joked. “He [Mulhare] hit me in the head and knocked me out” on the pickoff attempt.

Pacchioli, then 21 years old, was taken to Johnson City Memorial Hospital while, back at the ballpark, his Marion teammates struggled to get just one hit. However, the Mets managed a 2-1 win over the Yanks.

“I took the ambulance to the hospital, and they did all kinds of tests. I was there overnight. I was fine,” Pacchioli nonchalantly recalled.

He didn’t miss a single game. Marion was scheduled to play the third of a three-game series at Johnson City the day after Pacchioli was hit, the same day he left the hospital, but rain throughout the morning made the field too wet to play. So, the Mets boarded a bus and motored off to their next scheduled game in Harlan, Kentucky.

Pacchioli was right behind them.

“They [Mets personnel] got a car – I guess it was a taxi, I don’t know – but we met the team at Harlan,” Pacchioli recalled 55 years later. “We dressed in the hotel because the [Harlan] stadium was awful.”

A car ride through the rugged terrain of Northeast Tennessee into Eastern Kentucky must have been much more comfortable than the cramped bus his teammates rode, especially for a guy plunked in the head by a baseball, and especially for the 5-feet, 8-inch Pacchioli, who had a penchant for sleeping on the cold, metal luggage racks above his teammate’s heads.

“It was better than sleeping in those seats,” he said. “Those buses were terrible.”

Wait, there’s more about Lou

Pacchioli took a unique route to the minor leagues. He wasn’t drafted like many of his Mets teammates, but instead went to college after high school, earned a degree in health and physical education and became an elementary school teacher in New Jersey.

One day during his second grade PE class, he received a call during the school day.

“They [someone from the school office] came and got me and said ‘The Mets are on the phone,” Pacchioli said. “The people at the school didn’t even know I had played baseball.”

Mets executive Johnny Murphy was on the line from New York. “He said, ‘If [New York Mets General Manager] Eddie Stanky approves your contract,’” Pacchioli recalled, “’we’ll give you $2,500. We got to get you to spring training.’”

After getting a leave of absence approval from the school board office – “They were really good to me,” Pacchioli said of the board – he bought a car with his signing money and zoomed off to meet the Mets for training in Homestead, Florida.

After a month in camp with the Mets, Pacchioli was assigned to Greenville in the Class A Western Carolina League. His game there was built on speed. “I could really run,” he said. He hit .270 in Greenville, walked 53 times and swiped 30 bases. A coach there told him, “Lou, you have no signals [to steal bases], go on your own.”

Despite his contributions to the team, Pacchioli was sent down to rookie-league Marion.

“The excuse they gave me was they wanted me to work on switch hitting in Marion,” he said. He later discovered the Greenville team had other prospective ballplayers to look over. So, they sent Pacchioli to Marion to make room on the roster and make certain he was getting playing time.

“I was ready to quit. I was almost 22 years old, and I said ‘I’m not going.’ And the manager said, ‘Look if I don’t have you back here in two weeks, then you do what you want.’”

Lou didn’t quit. He trekked to Marion – he brought his Greenville uniform pants with him – and played a few weeks. “When I got there, I kind of had a chip on my shoulder because I was sent down, but I loved it there in Marion.”

Practicing switch hitting against the Marion pitching staff wasn’t an easy task. He had to bat, from an uncomfortable position on the left side of the plate, against future major leaguers Nolan Ryan and Jim Bibby, to name two.

“We had some kind of pitching,” the righty said. “They could all throw 90-plus [mph], and I was batting left handed and lining those pitches into the third-base dugout. [Players inside the dugout] were throwing towels at me,” Pacchioli said laughing, “White towels. They surrendered!”

The Pennsylvania native, who played mostly center field, contributed to the Marion team in an unusual way, too, for a player.

“We had no trainer,” Pacchioli recalled. So, because my degree was in health and PE, the manager [Pete Pavlick] asked me if I could help out with the training. I said sure.

“Pete said, ‘Go downtown to the pharmacy and buy what you need.’ So, I bought a lot of tape and stuff, and I used to give... after Nolan [Ryan] pitched, I’d give him rubdowns, got ice on his shoulder… and I’d make sure all the pitchers had the ice, which was hard to get, too. We had to buy that ourselves.”

“We dressed in the phys-ed locker room, Pacchioli continued. “Well, we walked down that big hill [from Marion Senior High School] to the stadium, and I got a chest for ice and bags, and I would wrap the guys with bandages, and basically that’s all we did. If we had a sprained ankle, I taped it.”

Pacchioli’s training days in Marion didn’t last long. Greenville kept its word and called him back. He was happy to return, but loved his short time in Marion. “It was a nice place to play,” he said. “The people there were so nice.”

Don’t kill the ump, please!

Umpires take a lot of abuse, but it’s usually nothing like the misery inflicted upon Tod Houston one August night in Marion. In the sixth inning of a game between Marion and Salem, a foul tip struck Houston in the neck and collarbone, knocking him “out for 10 minutes,” the Johnson City Press reported. Rescue workers, the paper noted, revived the umpire and he continued to work the game following the delay. Two innings later, another foul ball popped Houston in the neck, at about the same area as before. This time, there was no getting up. Houston was taken to the hospital in Marion for treatment. According to the Press, Houston, a longtime Appalachian League umpire from Bristol, Tennessee, was scheduled for a two-week tryout with the National League. I’m not sure if he ever got that tryout, but I’d love to know! If you have a tip about this or any other story for this newsletter, let me know at chadoz97@gmail.com.

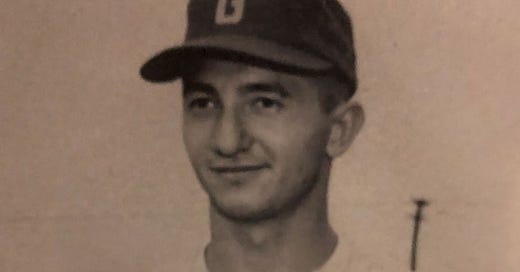

That’s it for now, back in a week when we’ll learn more about this photo:

Here’s a hint: It appeared in a 1967 edition of Life Magazine. That’s Marion Mets manager Birdie Tebbetts on the left ordering 50 cheeseburgers for his players after a game.

But, who is the woman working at the concession stand? Life Magazine didn’t tell us, so I had to do some digging.