Catching Nolan Ryan, a strategy behind the plate

Plus, don’t run on Ike Small’s rocket right arm... And, rain, lots of rain!

“No one in Minnesota threw like him.”

That’s Larry Wallin talking, still awed after all these years, about Nolan Ryan, the fireballing pitcher, who, before transforming into a tough-as-nails hall-of-famer, was drafted by the New York Mets out of high school in 1965 and started his professional baseball career with the rookie league Marion Mets in rural Southwest Virginia.

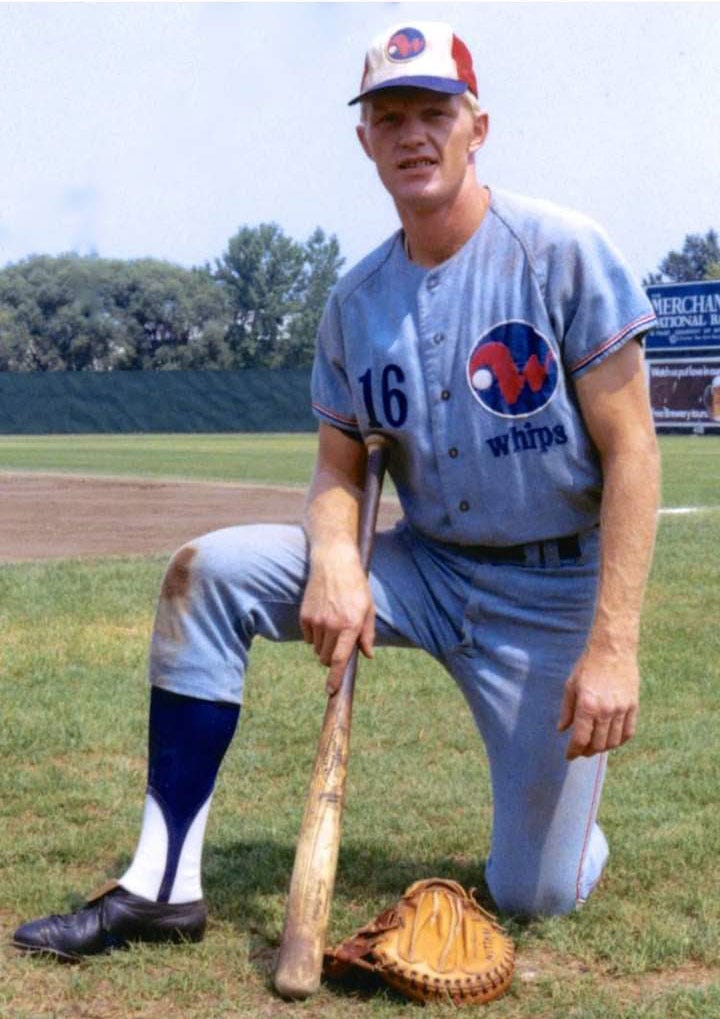

Wallin, 18 that year, joined the Marion team in July and was Ryan’s catcher for the last couple of weeks of the ’65 season.

“It was quite an experience for a kid out of Spring Lake Park, Minnesota,” Wallin told me in a phone interview in November 2019.

Wallin was playing and leading the Midwest Collegiate League in home runs and RBIs that season when, in mid-August, he was approached by a New York Mets scout named Walter “Wally” Millies following the league’s end-of-the-season all-star game.

“I want to talk to you about playing pro ball, if you’re interested.” The scout told Wallin.

He was definitely interested.

“That night, he [Millies] was at our house – I think it was a Thursday night – and I signed the contract and away I went. It was my dream to play professional baseball. So, I jumped at the opportunity.”

When Wallin joined the Marion ballclub, the Mets were playing on the road in Bluefield, Virginia. Mets manager Pete Pavlick told him he would not play that night. “Just meet everybody and get used to everything, and we’ll get you in a game the next couple of days,” Pavlick told Wallin. “You can warm up the pitcher tonight.”

So, the catcher grabbed his mitt, and walked to the bullpen.

“Of course, the lighting wasn’t the best in Bluefield, especially under the bullpen, and it was a night game. I warmed up a tall, skinny kid from Alvin, Texas,” he said with a chuckle, “named Nolan Ryan.”

The back of Ryan’s 1969 Topps baseball card claims the righthander was “blessed with blazing speed.” To further illustrate the point, the card back displays a cartoonish drawing of a scrawny, knobby-kneed catcher, looking bewildered at his mitt, which is blazing with towering flames.

Presumably, inside the mitt is a ball, that just seconds before, was discharged from Ryan’s right arm. Looking at it another way, you could argue the ball instead zipped straight through the mitt and landed somewhere on the moon. The catcher doesn’t appear to be in pain, but maybe he hasn’t yet realized his left hand is missing.

Wallin can sympathize with the comic catcher on the back of Ryan’s baseball card.

“He threw 101, 102 miles per hour,” Wallin said of Ryan. “Somebody said he was clocked at 104.”

Wallin’s first assignment with the Mets wasn’t an easy task.

“He was a little wild, and he threw exceptionally hard,” the big, strong catcher from Spring Lake Park said, recalling the moment nearly 55 years later. “I was sitting there 60-feet, 6 inches behind home plate, and I ended up moving back because I had a heck of a time catching him at that distance.”

Wallin had another strategy, too…

“I just didn’t blink,” he said. “Nolan scared the hell out of me!”

23 Scoreless Innings in Johnson City

The Johnson City Yankees learned a lesson the hard way one summer Saturday night in 1971.

Twice!

Don’t run on Ike Small’s rocket right arm.

Three frames into extra innings, the Marion Mets center fielder charged a single that came scorching across the pitcher’s mound and bounding up the middle off the bat of Johnson City Yankee Terry Whitfield. Small fielded the single cleanly and quickly fired the ball toward home plate, where 5-8, 190-pound Marion catcher Otto Dacosta snared the on-target throw and applied the tag to nail Johnson City runner John Williams, who had doubled moments earlier.

It would have been the winning run for the home-standing Yankees in the ballpark along Legion Street, but instead, Small’s throw preserved a 3-3 tie in the 12th inning of this August 15 contest.

The Yankees and Mets, both of which resided at (Yanks) or near (Mets) the bottom of the Appalachian League, had played eight scoreless and relatively lifeless innings before Marion tallied three runs in the top of the ninth off of Johnson City reliever Don Rogelstad.

In that inning, Marion second baseman Rich Puig doubled and later scored when left fielder Ed Grady hit a two-bagger of his own to give the Mets a 1-0 lead. First baseman Carlos Sagredo knocked in Grady for a 2-zip advantage and Marion tacked on a third run when Mark DeJohn drove home Sagredo with a single.

It must have been dejecting for Johnson City fans to watch their starter, righty Jody Norris, strike out 10 Mets and pitch eight scoreless innings, only to see the game slip away in the ninth.

But then came the rally in the bottom half of the inning, when the Yanks turned late Saturday into singles night, and finally produced a bit of scoring.

To the delight of hometown fans, the Yanks tallied three runs of their own in the ninth on singles by Whitfield, Mike Morgan, Steve Nepa and Larry Walker.

What had been an eight-inning pitchers’ duel between Norris and Marion starter Rex Phelps suddenly turned into a one-inning slugfest.

Neither team, however, could take control in the regulation nine innings, and the game continued late into the East Tennessee night.

The Yankees best chance for victory came and went in the 12th when Small gunned down Williams at the plate, much to the chagrin of the Johnson City fans who likely had plans to extend their Saturday night entertainment beyond the ballpark that Saturday night.

Their Yankees came close to ending the entanglement in the bottom of the 14th.

Julio Hernandez stood at third base with the winning run and Morgan at the plate. A single would win the game. Perhaps, too, a long fly ball would do the trick.

Morgan did the latter, knocking the ball to center field, where Ike Small stood, again waiting to load his rocket-launching right arm with the spheroid flying his way.

Small, who was named Marion’s most valuable player at the end of the ’71 season, caught the ball.

Hernandez kicked up dust as he pushed off third base, darting toward home plate with the game-winning run on his shoulders.

Small’s throw arrived just ahead of Hernandez. The catcher Dacosta, just as he done two innings earlier, made the catch and tagged out the runner to preserve the tie.

The clock had just struck 11 p.m., and into the 15th they went.

When both teams failed to score, the umpires suspended the contest until the next day because of Johnson City’s 11:50 p.m. curfew.

The Mets and Yankees arrived back to the field early Sunday afternoon with the same lineups they had employed the night before, with the exception of the pitchers, of course. And, just as they had done the night before, both teams laid goose eggs on the scoreboard in the 16th inning. Marion laid another one in the top of the 17th.

Met’s right-handed reliever Dick Holman pitched well in the bottom of the 17th, fanning Yankees batters Napa and Walker, but then he walked Ed Jayjack, giving Johnson City a spark.

Kevin Carr, pitching in relief for the Yankees, stepped to plate and smacked Holman’s pitch into right field, toward the ballpark’s infamous grassy hill, for a double. The speedy Jayjack tested the left arm of Marion right fielder Earnest Page – it wasn’t Small firing rockets this time – and Jayjack won, and so did the Yankees, 4-3.

When Jayjack crossed the plate, he ended a contest that played out of over two days and 4 hours and 14 minutes of game time. But, it wasn’t over between these two teams. There was still the regularly scheduled Sunday game.

It played out much like the first game with both teams going scoreless through seven innings. Ernie Destasi, the Mets’ Game 2 catcher, put an end to that nonsense in the top of the eighth when he launched a long solo home run out of Yankee Park. It gave Marion a 1-0 lead, and ultimately the win by the same score.

The game ended in an hour and 30 minutes. When both games were completed, the Johnson City Yankees and Marion Mets had played a total 26 total innings, 23 of which were scoreless.

Rain!

When I talk to someone who played for, coached or watched the Marion Mets, there’s one detail that seems to always come up in the conversation: Rain. Apparently, it rained a lot – I mean a lot – in Marion in the 12 years the Mets were in town, causing many delays and postponements.

In a way, that’s good for me because – I know this is odd – I enjoy researching and writing about weather’s influences on baseball games. Weird, right?

I plan to write a story in the near future that delves into some of the weather-impacted Mets games on the field and at the ticket gate.

In the meantime, if you share this same quirky interest, check out this non-Mets story I wrote for the Society for American Baseball Research, or SABR as it’s commonly known. The story is about a rowdy bunch of youngsters who stormed the field during two rain delays at Yankee Stadium in the wild summer of 1969. Oh, and it was Bat Day at the ballpark!

Here’s the beginning:

Amid the rain and slop, they hopped, slid, and swung their complimentary baseball bats through the air. They shouted; they laughed. They turned a famous ballfield into an untenable, unplayable muddy mess. Their shenanigans made the areas around first and second bases look like a pig’s pen – after the pig had tidied up a bit. The same mess surrounded home plate. The rowdy rapscallions made a slip-and-slide out of the tarpaulin, ripping holes in the $10,000 ground cover.

The rambunctious youngsters – there were about 2,000 of them – did this twice, the second occurrence minutes after the first. No one could contain them. A scoreboard message did little to dissuade them. The Voice of God called them to turn back, but they were determined, it seemed, to be the storm beneath the rain.

It was their fun in the mud. A blissful rebellion in the summer of 1969: Bat Day at Yankee Stadium.

That’s it for this week. I’ll be back next Friday with a story about the Marion Mets baserunner who dove for first, but landed in the hospital.